As will be clear to regular readers of this blog, we are concerned here to encourage the creation of the best possible records of small languages. Since much of this work is done by researchers (linguists, musicologists, anthropologists etc.) within academia, there needs to be a system for recognising collections of such records in themselves as academic output. This question is being discussed more widely in academia and in high-level policy documents as can be seen by the list of references given below.

The increasing importance of language documentation as a paradigm in linguistic research means that many linguists now spend substantial amounts of time preparing corpora of language data for archiving. Scholars would of course like to see appropriate recognition of such effort in various institutional contexts. Preliminary discussions between the Australian Linguistic Society (ALS) and the Australian Research Council (ARC) in 2011 made it clear that, although the ARC accepted that curated corpora could legitimately be seen as research output, it would be the responsibility of the ALS (or the scholarly community more generally) to establish conventions to accord scholarly credibility to such products. Here, we report on some of the activities of the authors in exploring this issue on behalf of the ALS and discuss issues in two areas: (a) what sort of process is appropriate in according some form of validation to corpora as research products, and (b) what are the appropriate criteria against which such validation should be judged?

“Scholars who use these collections are generally appreciative of the effort required to create these online resources and reluctant to criticize, but one senses that these resources will not achieve wider acceptance until they are more rigorously and systematically reviewed.” (Willett, 2004)

Follow

Follow

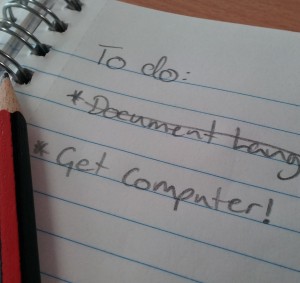

There are a (very) few linguists who advocate that researchers should go to the field with nothing beyond a spiral-bound notebook and a pen, though no one at the table was quite willing to go that far; all of us, it seems, go to the field with a good quality audio recorder at the very least. Without the additional recordings (be they audio or video) the only output of the research becomes the final papers written by the linguist, which are in no way verifiable. The recording of verifiable data, and the slowly increasing practice of including audio recordings in the final research output are allowing us to further stake our claim as an empirical and verifiable field of scientific inquiry. Many of us shared stories of how listening back to a recording that we had made enriched the written records that we have, or allow us to focus on something that wasn’t the target of our inquiry at the time of the initial recording. The task of trying to do the level of analysis that is now expected for even the lowliest sketch grammar is almost impossible without the aid of recordings, let alone trying to capture the subtleties present in naturalistic narrative or conversation.

There are a (very) few linguists who advocate that researchers should go to the field with nothing beyond a spiral-bound notebook and a pen, though no one at the table was quite willing to go that far; all of us, it seems, go to the field with a good quality audio recorder at the very least. Without the additional recordings (be they audio or video) the only output of the research becomes the final papers written by the linguist, which are in no way verifiable. The recording of verifiable data, and the slowly increasing practice of including audio recordings in the final research output are allowing us to further stake our claim as an empirical and verifiable field of scientific inquiry. Many of us shared stories of how listening back to a recording that we had made enriched the written records that we have, or allow us to focus on something that wasn’t the target of our inquiry at the time of the initial recording. The task of trying to do the level of analysis that is now expected for even the lowliest sketch grammar is almost impossible without the aid of recordings, let alone trying to capture the subtleties present in naturalistic narrative or conversation.