Peter Austin has raised his voice on this blog to ‘protect [his] legal rights and those of the Dieri people who have contributed to [his] knowledge of their language’ (source). He suggests that the PanLex project is guilty of ‘theft’ for using, without citation, data from a Dieri-English word list contained in his 1981 grammar of the Dieri language.1 He also implies that the PanLex project should not use the data without his permission.2

I think Austin ought to clarify exactly what he believes he owns and how he would justify the claim that it has been stolen. There are two aspects to copyright, commercial rights and moral rights. Austin has indicated that he is not interested in receiving royalties for the use of his data (source), although he would presumably not want anyone to make money from it (except his publisher, Cambridge University Press). There seems to be little danger of that, anyway: although I am not particularly familiar with the PanLex project and its financial backers, the administering Utilika Foundation appears to be a non-profit organisation (source).

Austin seems to be more concerned with asserting his moral rights. Under the Berne Convention, the main international copyright treaty that specifically mentions the moral rights of authors, the author of a work has

…the right to claim authorship of the work and object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action inrelation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation.

The PanLex project seems to have denied Austin his right to be recognised as the author of the word list by not providing a citation to his grammar, in which it originally appeared. This lack of citation appears to be a genuine oversight, however. The project maintains an extensive list of resources they are using in compiling their database. Although Austin’s 1981 grammar is not on the list, his and David Nathan’s online Kamilaroi/Gamilaraay dictionary is (a fact that Austin does not mention in his blog post). There is the possibility that the PanLex project has acquired the Dieri data through a secondary source that is listed but which does not acknowledge Austin’s original work properly.

The PanLex project clearly does not claim to be the original collector of the data and is not out to appropriate other people’s data with no acknowledgement, which is what Austin implies in his blog post. However, the project’s referencing definitely leaves something to be desired. As to possible distortion of Austin’s work that could be ‘prejudicial to his honor or reputation’, that is a separate issue about which he has not yet expressed an opinion.

What exactly is Austin claiming ownership over? Presumably not the entire Dieri language, but just the data contained in his word list. But what exactly is the data represented in his list? Is it just the equivalencies he has established between the Dieri and English words? It should be noted that raw data is not covered by copyright, although a particular representation of it is. This is a fact that Austin is aware of.3 The particular record of the equivalencies in his list is therefore protected by copyright. But we could also ask whether the list really is a creative work. A lot of effort certainly goes into acquiring and organising the knowledge required to produce such a list, but it could be considered merely sweat of the brow – that is, a work of diligence rather than creativity. If so, it would not be protected under US copyright law, but it would be under European copyright laws.4

Is Austin also claiming ownership over the actual words, as represented in his orthography? He uses the spelling of the Dieri word wadaŋaɲɟu to identify its origin in his book and the orthography is of his own devising. As a non-tangible system the orthography itself cannot be copyrighted, but perhaps particular instatiations of it could be. Should Noah Webster be cited every time someone writes the word ‘color’, because Webster was the first to propagate this spelling in his published work?

It should be pointed out that the PanLex project is not simply a copy of Austin’s 1981 word list. It is a new work that incorporates material from a large number of sources. It is what would be considered a ‘derivative work’. Under UK copyright law, the jurisdiction where Austin’s book was published and where he now resides and works, permission does appear to be required to use copyrighted material in a derivative work,5 although there are some possible exceptions where only excerpts are used. It could be argued that the Dieri words that appear in PanLex are excerpts from Austin’s book. They certainly do not represent a reproduction of the entire work. There may be no need to get permission in this case. But this is one for a judge to decide.

What are the potential implications of Austin’s assertion of ownership of the Dieri data? Since his publications contain a large amount of the Dieri linguistic data available outside the community, he could be seen as appointing himself as a gatekeeper to pretty much any non-primary research into the language. This is a point the President of the Utilika Foundation makes in the minutes of their 2011 AGM, which Austin cites as evidence of their ‘playing fast and loose’:

The creators of many resources assert rights that, taken literally, would prohibit a person reading a resource from later making use of what he or she had learned from it. From the beginning of the project, I have considered such usage prohibitions unenforceable, and I have considered our use of any resource to be the recording of facts asserted by it, in a novel form, not the creation of a copy of it and thus not copyright infringement.

Austin is not himself a fatcat publisher, movie studio or software company, but his wielding of the copyright bludgeon is reminiscent of their current practices. When we want to install software or sign up for an online service, we are confronted with ‘licence agreements’ consisting of several thousand words of legalese gibberish. We can’t go any further until we confirm that we have ‘read and agree’ to the terms.6 I can’t play region-coded DVDs that I have bought in Europe on my Australian DVD player. In the US, the publisher HarperCollins recently moved to force libraries to limit e-books to being borrowed only 26 times (source). The list goes on.

Using copyright to stop or hinder other research projects is perhaps a greater sin, however, even if we might not agree with the aims of the project or are not impressed by the quality of their work. Such abuses of copyright stifle innovation and the advancement of knowledge. If it were not for restrictive copyright, the underlying data that went into producing the ‘Culturomics’ database could have been made available to users, which would perhaps have improved its usefulness.

Now to help us all calm down, perhaps we should hear the message in Sesame Street style from Nina Paley:

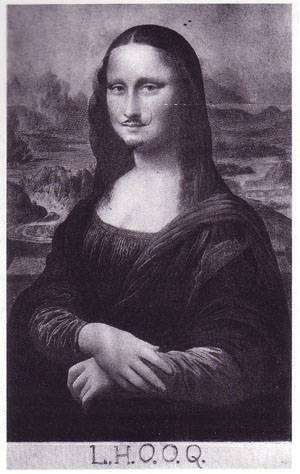

Image: Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., a derivative work, from Wikipedia

Thanks to David Nash for reading this post and suggesting some improvements, mainly restraint – you should have seen the first draft! Of course, what I have said here cannot be taken to reflect his views.

Notes

- Austin, Peter. 1981. A grammar of Diyari, South Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This is not the first time he has raised such concerns. He made similar complaints in a somewhat different case in an earlier blog post. Since this earlier case is not exactly parallel to the current one, my comments here cannot necessarily be taken to apply there.

- Austin comments: ‘The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) defines intellectual property as “creations of the mind: inventions, literary and artistic works, and symbols, names, images, and designs used in commerce”. Here “creations of the mind” refers to something that somebody created, and hence does not cover general knowledge like the meanings of words, or forms of a morphological paradigm (a particular definition, e.g., that found in a printed dictionary, would however be subject to intellectual property rights).’ Austin, Peter. 2010. Communities and Ethics in Language Documentation, in Austin, Peter, ed, Language Documentation and Description Volume 7, p.41.

- Wikipedia contains an article that addresses the main points.

- See the UK copyright service fact sheet P-22.

- And what do we really surrender in these agreements?

Follow

Follow

This posting says: “The PanLex project seems to have denied Austin his right to be recognised as the author of the word list by not providing a citation …”. It does seem that way, but in fact the PanLex project didn’t get the Dieri words in question directly from Austin’s publication. They came from another source that cryptically cites “Austin” as its source but hasn’t yet cited that source (or any of its 2,700 other sources) in full, because that intermediate source is an in-progress work with incomplete and not yet published metadata.

Details about this are in my essay, “PanLex Source Citation”. It ends with this Dieri example as a case illustrating how PanLex is designed to cope with various problems of source citation in a complex lexical database.

Jonathan

Unfortunately the cascading sloppiness of source referencing that you advert to is made even worse by materials being transferred from one data collector to another apparently without proper oversight. According to the Rosetta Project blog a database of Swadesh wordlists of Australian and New Guinea language materials compiled in 2002 by Paul Whitehouse has been incorporated into the Internet Archive. This appears to have included materials in Diyari, however the Internet Archive reference for the relevant Swadesh list erroneously gives me as the author! It also includes under Rights: “Swadesh list excerpted from “A Dictionary of Dyari, South Australia” by Peter Austin, 1981, Cambridge University Press”, not mentioning who did the excerpting and somehow managing to get the title of my book wrong! This particular compilation is given a Creative Commons License 3.0, however I did not agree to such a licence, which would permit sharing and remixing (with attribution). All of this seems to have been compounded when this material was passed on to you.

The immediate source of the PanLex vocabulary is not me or Whitehouse, but Linguist List’s LEGO project:

http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward.do?AwardNumber=0753321

Since the late 1990s, I have been collecting aboriginal vocabularies of New Guinea and Australia. This was merged with Whitehouse’s collection in the mid 2000s. A 2006 version of this material (since very significantly improved) was obtained by one of LEGO’s principals through his role as a programmer at MPI Leipzig.

The application for the LEGO NSF grant claims to have “secured [our] collaboration”:

https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=explorer&chrome=true&srcid=0B46sZfRAPzR9YTliNjgzN2QtZWZmZi00YjY5LTgwZWItYTkxMmIwZWFhMzAy&hl=en

This was an outright lie. Until early last year, I was not even aware of the projects’ existence. Since then, several serious deficiencies in LEGO’s handling of the material have come to light; the lack of proper citation is one of them. Having received at last count over $600k of taxpayer money, LEGO now claims to lack the means to address these shortcomings. Had the dataset been obtained in the normal way, these problems would not have occurred.

I have been informed by PanLex that proper citations will appear on their site if and when LEGO has provided them in their metadata.

The Google Docs link in Timothy Usher’s comment only works for people subscribed to the document. Publicly available information about the LEGO (Lexicon Enhancement via the GOLD Ontology) project can be found here. There is a Powerpoint presentation about LEGO here. Poornima and Good (2010) describes technical aspects of the project.

A web page by Jonathan Poole dated 25th February 2011 confirms that the PanLex data came from LEGO in an incomplete form:

Timothy Usher’s comment above states that “several serious deficiencies in LEGO’s handling of the material have come to light; the lack of proper citation is one of them”.

It seems to me that sorting out these issues of citation and attribution is important for the future of the field of language documentation and description (see my latest blog post) and in line with concerns about proper attention to what I have called “meta-documentation” in Austin (2010) and my conference presentation at the LSA annual meeting in January this year.

References

Austin, Peter K. 2010. Current issues in language documentation. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description, Vol 7, 12-33. London: SOAS.

Poornima, Shakthi and Jeff Good. 2010. Modeling and Encoding Traditional Wordlists for Machine Applications. Proceedings of the 2010 Workshop on NLP and Linguistics: Finding the Common Ground, ACL 2010, pages 1–9. [Available as a PDF here.]